Pathologists: Our Hidden Heroes

For those of us who’ve brushed up against the medical world, either as a patient or as a provider, we’ve become quite familiar with the word: pathology. But what exactly is pathology? What goes on behind the scenes? We may get a print out of our pathology report, or have our providers walk us through what this translates to as far as moving forward with our “kick cancer to the curb” plan, but there is so much that has to happen first…that has to happen in the heart of the lab…in order to bring you that critical data.

If you Google the word, the first thing that pops up is: “Pathology: the science of the causes and effects of diseases.” Pathologists examine tissue samples to determine what exactly is going on at the microscopic level. What secrets are held under the microscope? Is it cancer? If so, what kind? What grade? What is the tumor’s pathology? Estrogen and progesterone status? What about HER2?

Pathologists are the hidden heroes of our cancer journeys. What they do and the data they gather provides our surgeons, oncologists, and radiation oncologists with critical information that’s used to determine the most appropriate treatment plans for our specific cancer. Without these medical heroes working diligently behind the scenes, our healing from cancer would never take off. Patients who are triple positive, for example, will receive different care than those who are triple negative. Why? It’s because their cancers are different and need to be destroyed in different ways. You have to know what you’re fighting against before you can adequately fight against it. THAT is exactly what pathologists do. They sneak a peek at what that tumor is doing, how it grows, etc. THIS information is critical. Your life depends on it.

So, what do these MDs do? I can tell ya, it doesn’t work like a vending machine. You can’t simply insert tissue samples into the heart of the lab and have them instantaneously spit out a report. Oh no! There is great science at work in those labs! It’s biology at its best! And, sometimes that requires a smidge of time to examine and diagnose.

I was afforded an incredible opportunity earlier this week where I was able to do an interview for my podcast, Keepers of the Flame®, with a brilliant pathologist working at Memorial, Dr. Bruker. Although his interview will go live in April, I wanted to share a snapshot of what I learned. Dr. Bruker walked me through what happens from surgery to slides to diagnosis; and this information is not only fascinating, but it is 100% critical for your own cancer fight.

Here’s what happens:

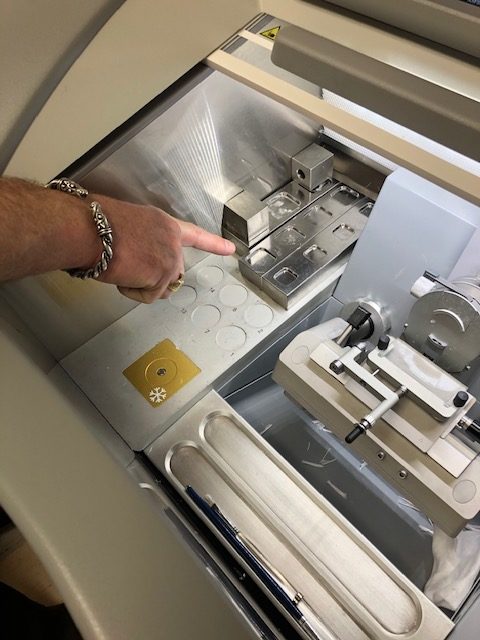

A patient is in surgery, and their breast surgeon examines their sentinel node. The question that determines how the surgeon proceeds is whether or not cancer made it to that node. If the answer is yes, then the surgeon may opt to do an axillary node dissection (where they remove all of the lymph nodes under that arm). If the answer is no – that lymph node is sparkly clean, then the surgeon can move on with the removal of the breast tissue. I used to think that they poked at the node…squished it around in their fingers a bit to see if anything felt ‘off.’ NOPE! Here’s what they actually do. The sentinel lymph node is removed, and a nurse walks it to a room next door. Here, the pathologist has a fresh tissue lab set up. (It’s fresh because that tissue JUST came out of the patient’s body). The pathologist puts the node in the little silver tray that’s being pointed to in Figure 1, and then uses a special spray that freezes it almost immediately. Once frozen, he hooks it up to that silver circle in Figure 2. Then, this machine can be set to slice the sample much like a meat slicer works in the deli. How thin do you want it? Usually, they set it at 2mm. Why? There’s a Goldilocks sweet spot here because the thinner you slice it, the more slides get generated, and this is all happening while the patient is under anesthesia. It’s dangerous for patients to stay under longer than need be, so pathologists work efficiently to maximize their efforts. Slicing at that 2mm thickness allows them to get a decent look at things without generating too many slides for that allotted time. In figure 3, you can see Dr. Bruker using a small brush to collect a sliced tissue sample. He then puts the fresh tissue sample on a slide, stains it, examines it under the microscope, and then phones the surgeon in the OR with the results.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Any of the other lymph nodes removed, along with the breast tissue itself gets sent to the lab and put in formalin (a commonly used fixative for histology). Pathologists then commence to making permanent slides that get examined further and are kept in their library for 10 years. (The library has drawers looking oddly familiar to card catalogs, though tailored in size for slides).

They cannot make slides of the entire breast that was removed; that would yield an unruly number of slides. To put this in perspective, Dr. Bruker shared with me that a professor once tried to create slides for an entire prostate (which is a smaller organ than a breast). The professor was unable to complete the task, stopping at 80,000 slides!! That’s insane! And if you think about it, ALL of that tissue isn’t the target area. So, in the figure below you can see one of his colleagues searching through a removed breast for the cancer. Much of this process involves a combination of science and art. She has to use her senses and know what she’s feeling for. In the second photo below, she’s found the cancer. Sometimes, after a biopsy is done physicians insert a clip to mark the spot that was biopsied. (I called this my spec of glitter, but of course that’s not technical). In the pathology lab, they can often locate the cancer by finding these clips. Another strategy that they use is taking x-rays of the tissue. She’ll lay the breast tissue on a tray, walk across the hall to imaging, and have an x ray done. This will aide her in searching the tissue for any other specs of concern.

Examining the breast tissue

Finding tumors

They also have little one-inch trays that have the patient’s data tagged on the edge. When tissue containing cancer is extracted from the specimen, it is placed in these little trays. A few other procedures are done, including running it through a tissue processor (photo below). Afterwards, these trays, each holding an individual sample cut from the specimen, are taken to embedding. The machine (picture below) that does this has hot wax squirt onto the sample in the tray, creating a block (picture below). This block can be sliced and used to make slides in a similar fashion to how the fresh tissue slides were made.

Tissue Processor

Embedding machine

Block with tissue sample made from embedding

Once slides are made, the machine pictured below is used to determine the estrogen and progesterone status. (Again, this is critical information for your treatment plan). An antibody of estrogen is applied to one of the slides and then the machine does its thing. (The same is done for progesterone). HER2 status can be determined in this manner IF it is strongly positive or negative. If the HER2 is in that grey middle zone, then they do another procedure: FISH.

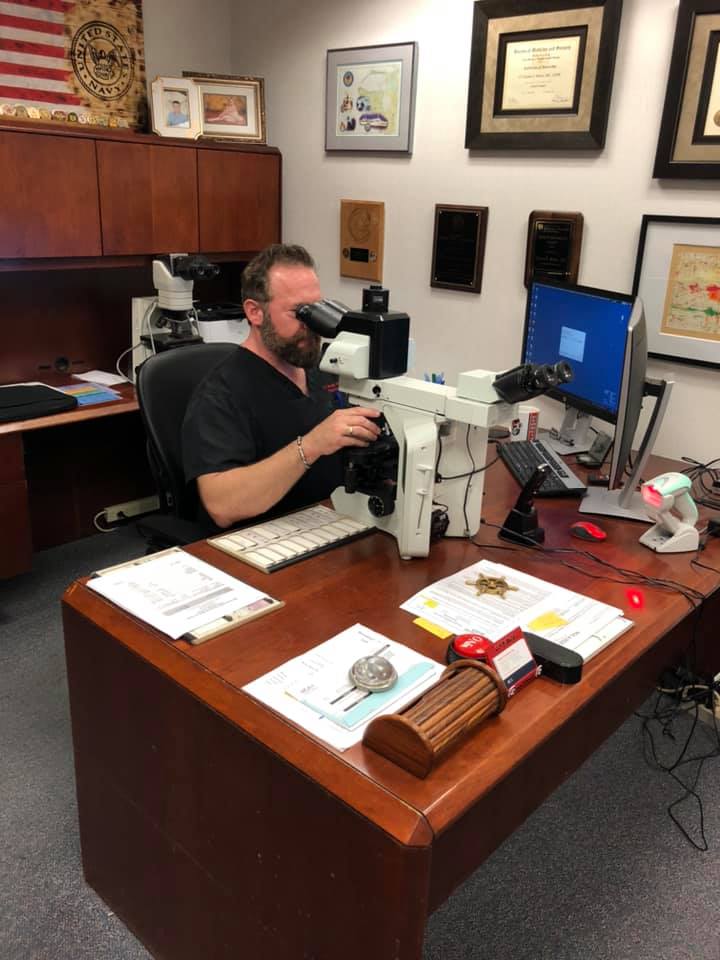

Then, all of these slides are taken to the pathologist where he studies the cellular activity. What does he see happening under the microscope?

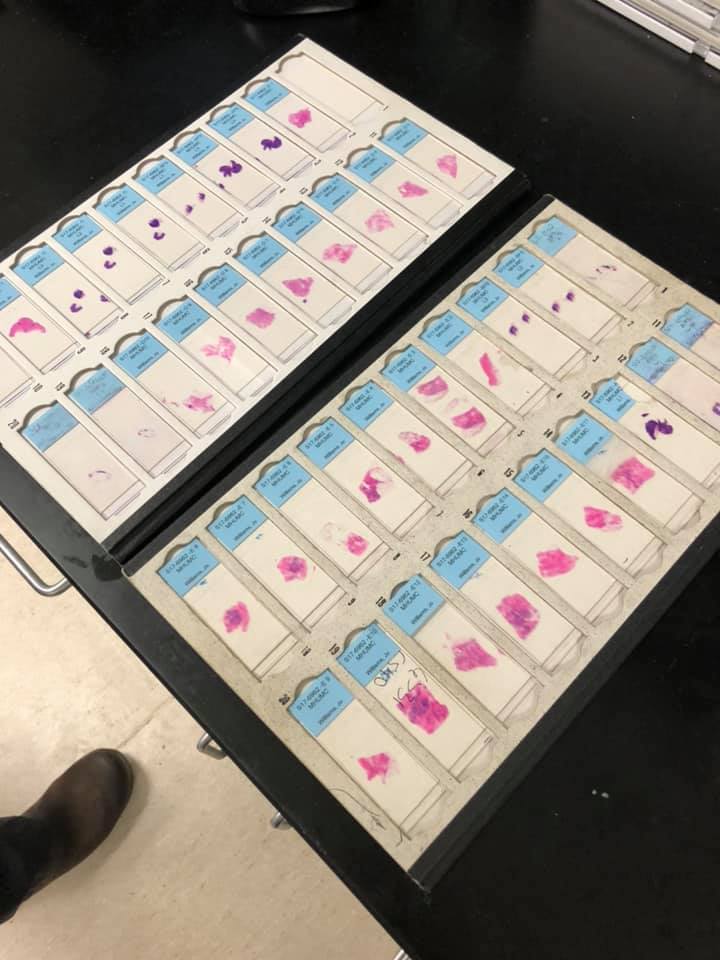

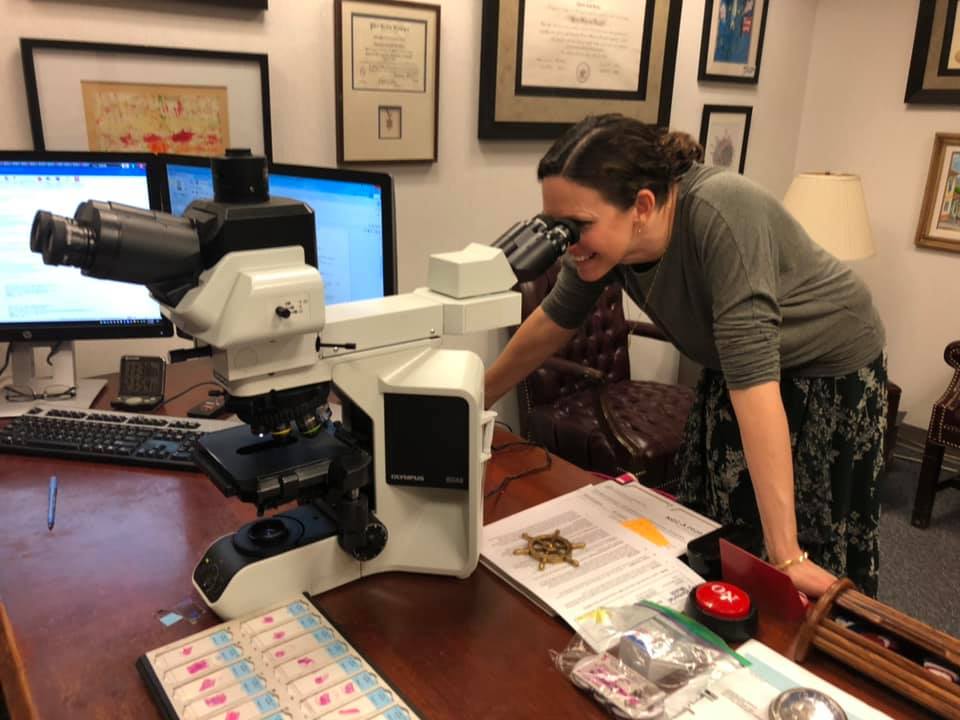

The two trays of slides below are of my cancer. That’s MY cancer sitting on that lab desk! We were able to look it up, go to the “card catalog”, and take them to the microscope. I was fortunate enough to have Dr. Bruker let me look for myself, and in doing so, he explained what we were seeing and what pathologists look for.

My cancer on slides

Pathologist examines slides

I get to take a peek at my cancer

Breast cancer comes in so many different flavors, characterized by location, size, lymph node involvement, hormone and HER2 status, as well as something called the grade. (This is different than cancer stage). Tumors with a high grade (2-3) are typically more aggressive; and low grade (or 1) are less aggressive.

The tumor grade is based off of how wonky-eyed those cancer cells look in comparison to normal breast tissue cells. Mine was a grade 3 – crazy cancer boogers. The tumor grade is assessed based on three criteria: tubule formation, nuclear grade, and mitotic rate. In my breast tissue, here’s what we saw:

The tubule formation: when it’s gone sour and not behaving properly, those cells look oblong and stacked next to one another – looking like flat sardines playing charades and trying to mimic sedimentary rock. (That’s my description…but essentially they’re not looking like normal cells).

The nuclear grade: The pathologists look to see how big the nuclei of the cells are. Also, how deformed is that nuclear envelope? My cells? Yep, I saw some giant nuclei and some struggling envelopes.

What about mitotic rate? Mitosis is cell division. This happens all the time with our somatic cells. We want that. BUT!! We do not want that happening when those cells are cancer. We don’t want cancer cells dividing because that’s indicative of the cancer growing. In these slides, I was able to see what was supposed to me metaphase happening in several of these cells. Metaphase is when the chromosomes line up along the middle right before the cells starts to split (anaphase, telophase, cytokinesis). With these wonky-eyed cancer cells, they don’t follow formation quite like their law abiding normal cell neighbors. Picture Kindergarten Cop when Arnold Schwarzenegger was trying to get everyone out of the school for a fire drill. It was like herding cats. He was trying. Same thing with these chromosomes. They’re trying to do metaphase properly, but they don’t quite get it. Pathologists call these mitotic figures. The more mitotic figures that have been captured on these slides, the higher the grade.

There is an amazing world of biology happening in our bodies: in all of our bodies, those with and those without cancer. Still, to see what’s happening with those cells inside your precious tissues…well, that is quite miraculous. Studying this, examining and diagnosing from this microscopic level …doing what pathologists do…it is not only genius, it’s a vital step in saving your life. It takes a team to fight cancer: surgeons, oncologists, radiation oncologists, AND pathologists.